My daughter has been living in Melbourne for the past year. I asked her to share her experience of isolation, restrictions, and lockdown.

This is her story.

A COVID-19 Calendar

March

My coworker is a self-confessed hypochondriac. The fact that the world is slowly descending into coronavirus chaos doesn’t help.

The morning we’re sent home from work, her voice breaks like she’s about to start crying. She’s afraid. I try my best to push her fear away, but it stubbornly wraps its spiny tendrils around me.

I smile a big smile as I leave, with my laptop, charger, and belongings in hand. “It’s okay,” I say. “We’re working from home now.” But her fear makes her deaf. She doesn’t hear my attempt at reassurance.

The next day, I get in the car with my friend and we drive for 10 hours until the city is a forgotten prison far behind us. The comfort of her childhood home in the countryside caresses us back to some level of composure.

Everything is unsettling and unknown. My dad wants his car back but the borders are closed. I’m not afraid of getting sick but I’m afraid of what people might do to each other. When does panic-buying turn into panic-fighting?

My anxiety goes from zero to post-apocalyptic in the time it takes Jacinda Ardern to coin ‘the bubble’. I shake and I cry and I lie in numbing silence, not sure what to do, where to go, whether my job will last, how I’ll get through this, how we’ll all get through this.

One dark night brings with it a nightmare. I can’t remember what happened but I’m terrified. In my dream, I bang my fist against the wall, again, again, again, hoping my friend – asleep on the other side of it – will hear me. She doesn’t. I don’t wake up.

But in the morning, I tell her about my dream. I tell her I couldn’t move, couldn’t run, couldn’t speak or scream or cry out for help. I tell her that my dream self hit the wall hard, in utter desperation, hoping one of us would wake up.

She gives me a strange look. As the yellow morning light streams in through the kitchen windows, she says, “I heard you.”

April

We go back to Melbourne for a job my friend doesn’t get. She comes over after the interview, upset and in need of my comfort blanket. My brother, from a country away, orders us Uber Eats for dinner. We are glad to have someone who cares.

I fall into a new routine of staying locked away in my room. It’s not something I have ever done before, but there is nowhere else to go.

I get back into the habit of walking my flatmate’s dog every day. He is a big white cloud carrying the sun around with him. Even in the dark, he is easy to spot. His name in Japanese means happiness.

But I just call him Scooge.

May

My depression has struck me again, hard, in the chest. Life hasn’t felt this overwhelmingly hopeless since 2019 was at its end. I don’t want to leave the house. I don’t want to leave my room. I am distant, lost. Unrecognisable.

‘Shame’ and ‘supermarket’ are two words that start to sound the same, feel the same. I blink before my eyes have a chance to see my reflection in the automatic glass doors, desperate to throw my body away before the sight of it can catch me.

I drive to the lookout and call my mum. It’s dark. I don’t pay for parking. We FaceTime, but she can’t see me. She can’t see my tears. She can hear them, though. She doesn’t know what to do.

Neither do I.

June

I see a hypnotherapist. It works insomuch as it doesn’t, and I learn that acceptance is the only way I can move forward.

I start to explore again, to dip my toes into the natural recesses of the city. I go back to the beach, to the forest, to the hills. I see my friends in person and not on a screen. I sit down for dinner in restaurants and I brave the mall to buy a pair of Dr. Martens.

These shoes will make me happy, I think. These shoes and a tan and a summer dress and a surfboard. I walk and I talk and I smile and I sing, but I don’t laugh.

It’s been a long time since I laughed.

July

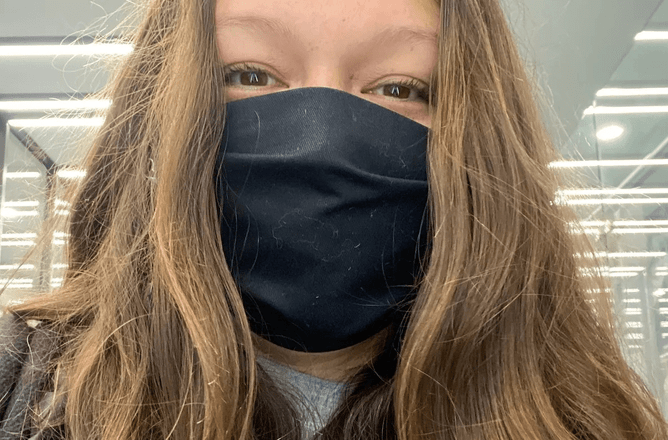

My friend tells me that masks will be mandatory soon. I ignore her, hoping that my ignorance will make it not true. But on a Wednesday, my ignorance is proven wrong (as ignorance often is).

I buy 5 reusable masks. Wearing them makes it hard to breathe. I complain to my mother about it, and she points out that nurses have to wear them on shift for hours at a time. I stop complaining.

The city moves back into stage 3 restrictions. Not much changes for me except my weekends, which now mirror my weekdays. I watch Netflix in bed, eat Maltesers and McDonald’s, and socialise only with Scooge. I can handle this, I think. This is not so bad.

Then Melbourne introduces stage 4 lockdown.

I’ve been working from home since mid-March, confined to four walls for five months. My boss has told me that once JobKeeper ends in September, so too will my role with the company.

I am relieved to finally be free, but anxious about finding a new job in an already over-saturated market. As an unemployed Kiwi living in Australia, I will not be eligible for financial aid. This country I call home will no longer have a place for me beneath its roof.

My focus on the task at hand is deteriorating. My eyes have shadowed, bruised half-moons beneath them. I am slow, sleepy. I have forgotten what it feels like to stand steady on my feet and turn my face up to the sun.

My routine is a lonely one, but Scooge and I walk every day, and he is not lonely. Saturday nights are especially quiet with neither of my flatmates home, and I am glad for the fluffy white mess of him hanging around to keep me company.

Scooge likes to dance, but only with a partner. He sits on the couch when I read, and sometimes we watch tv together. I make sure his bowl always has fresh water and he makes sure I always have someone to talk to.

He feels more like mine than anyone else’s. I wish he were.

August

My flatmate tells us that he is giving his dog up for adoption. I am a confusing medley of emotion, sad because I don’t want Scooge to leave but happy because hopefully where he goes, he will become a priority and not a second thought.

I want to adopt him but I don’t know if I can. It’s not just a financial thing. I am a free spirit and when the time comes to wander again – when the time comes that I am capable of wandering again – I’m worried that he might not be able to come with me.

It’s my birthday on Sunday and I will be spending it, for the most part, alone. Scooge and I will go for our mandatory 1-hour walk, and then we’ll open presents that mum sent over. I will eat cake and ice cream, and do what I always do. Not much of anything.

My life in lockdown has been defined by a dog who isn’t mine, a Netflix account borrowed from a friend, and a job that has drained and doused and destroyed whatever creativity I once had.

It feels like an ending, but not the forever kind – it’s more special than that. It’s the line in the sand that you can’t wait to reach because you know that stepping across it will bring you to the wildest and most colourful of beginnings.

That, and a quiet, reverent promise: you will find yourself again.